“No battle plan,” said Helmuth von Moltke, “survives contact with the enemy.”

But that doesn’t mean you go into battle without one.

For authors, the outline is our battle plan and the enemy is the writing itself. When you start with some form of an outline, you go into a project knowing, at least, what you’re trying for. You know what to write first, then you know what to write next, and you know where the whole thing is going to end.

But then maybe that should be:

When you start with some form of an outline, you go into a project with at least a general idea of what you’re trying for. You know what to write first, then are pretty sure what to write next, and have some vague concept of where the whole thing might come to an end.

Susan Sontag described that kind of rough battle plan this way:

From the beginning I always know what something is going to be; every impulse to write is born of an idea of form, for me. To begin I have to have the shape, the architecture. I can’t say it better than Nabokov did: “The pattern of the thing precedes the thing.”

And that’s the pattern of the story, not the outline itself. I fear that, sometimes at least, when I use that word “outline” what a lot of you are seeing is that old fashioned hyper-templated Outline you were probably assaulted with in high school with its rigid hierarchy of Arabic numerals, Roman numerals, lowercase and capital letters… You can try that on a novel if you like, but I never have, and never will.

As I try to do with words like “hero,” “villain,” and “conflict,” for me, “outline” just means some kind of a plan, some version of a skeleton upon which a novel can be built. It can be, as J.G. Ballard describes, more of…

J.G. Ballard

…a brief synopsis of about a page, and only if I feel the [short] story works as a story, as a dramatic narrative with the right shape and balance to grip the reader’s imagination, do I begin to write it. Even in the Atrocity Exhibition pieces, there are strong stories embedded in the apparent confusion. There’s even the faint trace of a story in “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan,” and the other sections at the end of the book. In the case of the novels, the synopsis is much longer. For High-Rise, it was about twenty-five thousand words, written in the form of a social worker’s report on the strange events that had taken place in this apartment block, an extended case history. I wish I’d kept it; I think it was better than the novel. In the case of The Unlimited Dream Company, I spent a full year writing a synopsis that was eventually about seventy thousand words long, longer than the eventual novel. In fact, I was cutting down and pruning the synopsis as I wrote the novel. By synopsis I don’t mean a rough draft, but a running narrative in the perfect tense with the dialogue in reported speech, and with an absence of reflective passages and editorializing.

I’ve told the story before of receiving an outline from Lynn Abbey that was 104 pages long. It began as a rough plot synopsis then she would build it, layer by layer, into the finished work. R.A. Salvatore would also send a rough synopsis so I’d know what he was shooting for. Other authors, including myself, would craft a fairly detailed (but rather fewer than 104 pages) chapter by chapter outline, generally “plot heavy,” which is not a bad thing at this point in a novel’s lifetime, as Grace Paley, told the Paris Review in 1992:

Plot is nothing; plot is simply time, a timeline. All our stories have timelines. One thing happens, then another thing happens. What I was really talking about in that story was having a plot settled in your mind: this is the way the story’s going to go. In the next thirty pages or so, this will happen, this will happen, this will happen.

And even though we should always be open to new ideas—better ideas—along the way, which is where the battle plan falls before the enemy’s relentless advance, an outline, however rough, can also serve to keep the author on track with the actual process of writing the thing, and not just what plot beat comes next. The brilliant Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami told The Atlantic:

Every time I write a new novel, I tell myself, Okay, here is what I’m going to try to accomplish, and I set concrete goals for myself—for the most part visible, technical types of goals. I enjoy writing like that. As I clear a new hurdle and accomplish something different, I get a real sense that I’ve grown, even if only a little, as a writer. It’s like climbing, step-by-step, up a ladder. The wonderful thing about being a novelist is that even in your 50s and 60s, that kind of growth and innovation is possible. There’s no age limit. The same wouldn’t hold true for an athlete.

And even then, athletes train, generally speaking, according to a plan.

So however you see it, just a set of notes to get you started, a synopsis that lets you at least feel like you know where you’re trying to go, or a chapter by chapter outline designed to keep a complex story full of twists and turns from running off the rails, don’t sleep on the outline. It can keep you on track even while it keeps your story on track.

At least, until you get all those better ideas along the way, and revise the battle plan accordingly.

More on outlines and outlining…

Pantsing My Way Through an Outline

—Philip Athans

Did this post make you want to Buy Me A Coffee…

Follow me on Twitter @PhilAthans…

Link up with me on LinkedIn…

Friend me on GoodReads…

Find me at PublishersMarketplace…

Check out my eBay store…

Or contact me for editing, coaching, ghostwriting, and more at Athans & Associates Creative Consulting?

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

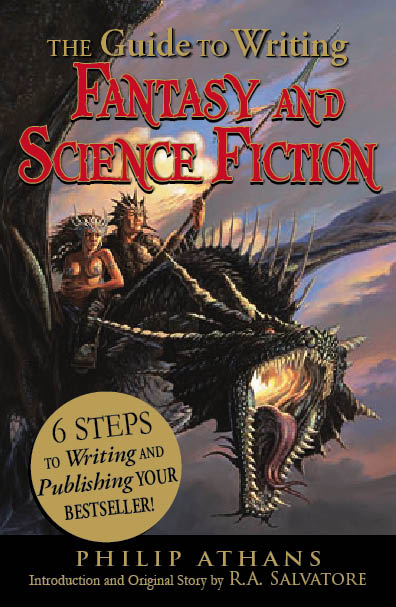

Science fiction and fantasy is one of the most challenging—and rewarding!—genres in the bookstore. But with best selling author and editor Philip Athans at your side, you’ll create worlds that draw your readers in—and keep them reading—with

When I was in law school, one of my professors required a précis before we wrote any paper. I always thought that was a pretensious word for a summary or outline.

Pingback: DO CHARACTER ARCS ACTUALLY MATTER? | Fantasy Author's Handbook