You know, by now, how strongly I feel about the importance of strongly motivated characters—heroes and villains alike. Last October, I got into this in “Why? The Heart of Character Motivation” when it comes to villains:

Evil, like good, is specific to an individual and is something that comes from deep inside, from a mix of nature and nurture, and is visible in that individual’s speech and deeds. And often, the worst acts are perpetrated not by someone with “evil intent,” but by someone with perfectly benevolent intentions who somehow screws up, misinterprets, acts out of fear or some other personal weakness.

In other places I’ve described the heart of well-motivated characters as an effort to fill some hole in themselves, to find a missing piece in their lives, their psyches, their souls, that they believe can be filled by… whatever your story is about: the lust for power, the final defeat of Evil, etc. But just “I want to be the king” simply isn’t enough. There has to be a reason that this particular person feels he has to be the king. This deeper level gets to what I believe Italo Calvinomeant when he said, “Novelists tell that piece of truth hidden at the bottom of every lie.”

The lie is I want to be king because it’s my birthright and I would be awesome at it. The truth is that my father once told me I would never be king and if I can prove him wrong I can finally feel like a whole person, like I’ve beaten him in some kind of epic struggle, even if that struggle exists entirely in my imagination, based on a wild misinterpretation of one conversation had forty years ago. The truth, it turns out, almost never matters when it comes to what we really feel, or as Franz Kafka once wrote, “The outside world is too small, too clear-cut, too truthful, to contain everything that a person has room for inside.”

So then what is that missing thing your character is trying to reclaim, or claim for the first time…? Could it be what the Portuguese call saudade—a longing for a past happiness that may have been entirely invented? Maybe.

Indeed, it could be anything, but if you can describe it in one word, I don’t think you’re there yet. How to get there… that’s the hard part. Do we start with what’s missing in ourselves? Hernan Diaz said,

Writing is a monstrous act because it implies a metamorphosis. Writing, to me, is an attempt at becoming someone else. Every novel is a long way of tracing an x, of crossing myself out. I don’t want to be on the page. I want someone else to be there—someone else to “happen.” Still, despite my best efforts, I always remain, deformed and disfigured. The final paradox, of course, is that I am the one striking myself out. And isn’t this duality also quite monstrous?

But we also have to venture outward from ourselves. How else could we imagine what might be missing in someone? “I could answer,” Susan Sontag once said, “that a writer is someone who pays attention to the world.”

So, pay attention!

It’s actually fairly rare, in my experience, that a character actually comes out and says: This is why I’m really doing this. These holes we try to fill in ourselves rarely make themselves known to us, and likewise stymie everyone around us. But sometimes we figure it out, just like the protagonist of Harlan Ellison’s 1966 short story “Turnpike,” about a truck driver who meets a woman on a cross country trip, they follow each other for mile after mile, day after day, and things get weird…

And then, as we passed over the line into Ohio, with night bombarding us, I got the most eerie feeling. What was pulling me on like this? Why was I so hot to get this little teenie-bopper? I’d seen the swingers before; they peppered the bars off Times Square every Saturday night. In from Jersey where the age limit was higher. But why this one? What song had she been silently singing that got my groin bell bonging, what snail crawling through my inward side, what height I hadn’t reached, what door slammed when I was a child, what act I’d begun and never completed, what vision I’d had that had been shattered for me… what meal had turned rancid in my belly, what bill had never been paid, what game had I chanced everything and been taken like a patsy… what wind had chilled me, what sun had scorched me… all uselessly, all senselessly the day of graduation when I’d run shrieking into the fields of reality and never gone back for the passport into the big time? What was it that made me follow through the night that blue Mustang with the waving banner of yellow hair? What was it, and would it kill me?

Whether or not this fevered introspection is enough to set this guy straight…? That would spoil an exceptional story you should go out and read for yourself. But in this example we see that this idea of a deeper motivation needs to be grounded in a world, either our own now or in the past or future, or one of your own making. Whatever is missing in a character will tend to be filled from what’s available to that character in that time and place, because it’s something from that time and place that’s missing in the first place. Consider this from “Against Authenticity” by Bo Winegard:

Even a person’s most sacred beliefs—those about God and the relationship between humans and the cosmos—are inextricably connected to culture. The ancient Mediterranean worshipper of Isis and Osiris may have been a zealous Protestant in 17th-century Germany and a combative skeptic in 21st-century America. Similarly (though less consequentially), a champion of free verse in the 20th century may have been a stickler for meter and rhyme in the 14th. Dante wrote as he did because of his surrounding culture. Five hundred years later, he would have written differently. The same holds for virtually every imaginable belief and activity, from the mundane to the sublime.

I want to follow this woman and steal her away from the guy she’s traveling with because…?

I want to be Queen of Andals and the First Men because…?

I will have my revenge against the Baron Harkonnen because…?

“I,” the character, may not ever be able to answer that question, but we, the authors, better put some quality thought into it.

—Philip Athans

Did this post make you want to Buy Me A Coffee…

Follow me on Twitter @PhilAthans…

Link up with me on LinkedIn…

Friend me on GoodReads…

Find me at PublishersMarketplace…

Check out my eBay store…

Or contact me for editing, coaching, ghostwriting, and more at Athans & Associates Creative Consulting?

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

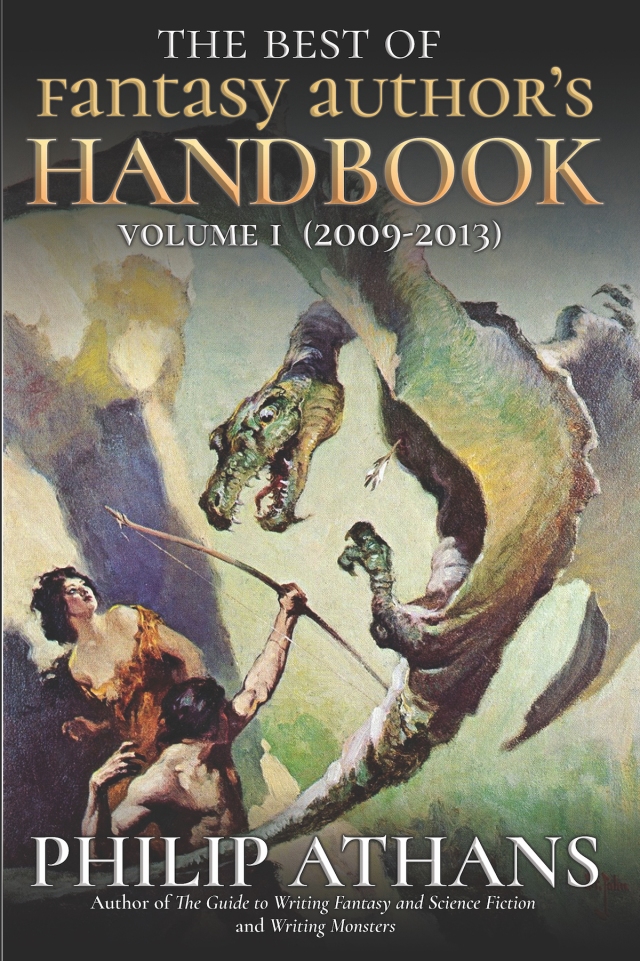

Editor and author Philip Athans offers hands on advice for authors of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and fiction in general in this collection of 58 revised and expanded essays from the first five years of his long-running weekly blog, Fantasy Author’s Handbook.