I read what other authors have to say about writing. I wouldn’t say I read that “obsessively,” but definitely “regularly.” You should be doing that to—and, I guess, if you’re reading this right now . . . you are!

Though I don’t do guest posts here at Fantasy Author’s Handbook, I thought maybe this week I’ll more or less turn it over to a few other authors—from articles and interviews of theirs I’ve read , on the subject of ideas and inspiration.

How does a story actually begin to form in an author’s mind? How does it move forward from vague concept to finished prose? This is the Big Mystery out of all the many and varied Big Mysteries in the realm of creative writing.

Where do ideas come from? What is the source of human creativity? I have no idea, so let’s see what a few smart people have to say . . .

Neil Gaiman tackles this head on in “Where Do You Get Your Ideas?” where he concentrates on an author’s inner dialog:

You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it.

You get ideas when you ask yourself simple questions. The most important of the questions is just, What if . . . ?

(What if you woke up with wings? What if your sister turned into a mouse? What if you all found out that your teacher was planning to eat one of you at the end of term—but you didn’t know who?)

Another important question is, If only . . .

(If only real life was like it is in Hollywood musicals. If only I could shrink myself small as a button. If only a ghost would do my homework.)

And then there are the others: I wonder . . . (‘I wonder what she does when she’s alone . . .’) and If This Goes On . . .. (‘If this goes on telephones are going to start talking to each other, and cut out the middleman . . .’) and Wouldn’t it be interesting if . . . (‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if the world used to be ruled by cats?’) . . . Those questions, and others like them, and the questions they, in their turn, pose (‘Well, if cats used to rule the world, why don’t they any more? And how do they feel about that?’) are one of the places ideas come from.

Often ideas come from two things coming together that haven’t come together before. (‘If a person bitten by a werewolf turns into a wolf what would happen if a goldfish was bitten by a werewolf? What would happen if a chair was bitten by a werewolf?’)

Isaac Asimov, the Grand Master of Grand Masters of science fiction, wrote an essay called “How Do People Get New Ideas?“ in 1959 that, though more concerned with the development of new scientific theories, still has a lot to tell us about creativity in general and the dichotomy of creating as a strictly personal, isolated pursuit and the concept of the “cerebration program,” which we might call a “writers group”:

My feeling is that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required. The creative person is, in any case, continually working at it. His mind is shuffling his information at all times, even when he is not conscious of it. (The famous example of Kekule working out the structure of benzene in his sleep is well-known.)

The presence of others can only inhibit this process, since creation is embarrassing. For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display.

Nevertheless, a meeting of such people may be desirable for reasons other than the act of creation itself.

No two people exactly duplicate each other’s mental stores of items. One person may know A and not B, another may know B and not A, and either knowing A and B, both may get the idea—though not necessarily at once or even soon.

Furthermore, the information may not only be of individual items A and B, but even of combinations such as A-B, which in themselves are not significant. However, if one person mentions the unusual combination of A-B and another the unusual combination A-C, it may well be that the combination A-B-C, which neither has thought of separately, may yield an answer.

It seems to me then that the purpose of cerebration sessions is not to think up new ideas but to educate the participants in facts and fact-combinations, in theories and vagrant thoughts.

But how to persuade creative people to do so? First and foremost, there must be ease, relaxation, and a general sense of permissiveness. The world in general disapproves of creativity, and to be creative in public is particularly bad. Even to speculate in public is rather worrisome. The individuals must, therefore, have the feeling that the others won’t object.

If a single individual present is unsympathetic to the foolishness that would be bound to go on at such a session, the others would freeze. The unsympathetic individual may be a gold mine of information, but the harm he does will more than compensate for that. It seems necessary to me, then, that all people at a session be willing to sound foolish and listen to others sound foolish.

If a single individual present has a much greater reputation than the others, or is more articulate, or has a distinctly more commanding personality, he may well take over the conference and reduce the rest to little more than passive obedience. The individual may himself be extremely useful, but he might as well be put to work solo, for he is neutralizing the rest.

The optimum number of the group would probably not be very high. I should guess that no more than five would be wanted. A larger group might have a larger total supply of information, but there would be the tension of waiting to speak, which can be very frustrating. It would probably be better to have a number of sessions at which the people attending would vary, rather than one session including them all. (This would involve a certain repetition, but even repetition is not in itself undesirable. It is not what people say at these conferences, but what they inspire in each other later on.)

For best purposes, there should be a feeling of informality. Joviality, the use of first names, joking, relaxed kidding are, I think, of the essence—not in themselves, but because they encourage a willingness to be involved in the folly of creativeness. For this purpose I think a meeting in someone’s home or over a dinner table at some restaurant is perhaps more useful than one in a conference room.

Probably more inhibiting than anything else is a feeling of responsibility. The great ideas of the ages have come from people who weren’t paid to have great ideas, but were paid to be teachers or patent clerks or petty officials, or were not paid at all. The great ideas came as side issues.

To feel guilty because one has not earned one’s salary because one has not had a great idea is the surest way, it seems to me, of making it certain that no great idea will come in the next time either.

For a more spiritual take, in the introductory material for his graphic novel collection Screaming Planet, mad genius Alexandro Jodorowsky wrote:

I admit that I would often get down on my knees and pray to my unconscious: “I can’t imagine my way out. Please, give me the solution!” After a while, the solution would pop into my mind. I do mean “pop,” because I wasn’t crafting it. I just contented myself to receive it fully formed in my mind. In those privileged moments, my heart would beat faster and with an exquisite joy I would exclaim: “Thank you, my unconscious! Thank you for this gift!”

And in the additional material for my online Horror Intensive (which is starting up again in a couple weeks), I quote the great Stephen King three times on the nature, source, and wellspring of ideas. The first is from an interview with Rolling Stone:

I can remember as a college student writing stories and novels, some of which ended up getting published and some that didn’t. It was like my head was going to burst—there were so many things I wanted to write all at once. I had so many ideas, jammed up. It was like they just needed permission to come out. I had this huge aquifer underneath of stories that I wanted to tell and I stuck a pipe down in there and everything just gushed out. There’s still a lot of it, but there’s not as much now.

Next, from a Paris Review interview in which he discusses commenting on, or being inspired by, current events or trends:

Take Cell. The idea came about this way: I came out of a hotel in New York and I saw this woman talking on her cell phone. And I thought to myself, What if she got a message over the cell phone that she couldn’t resist, and she had to kill people until somebody killed her? All the possible ramifications started bouncing around in my head like pinballs. If everybody got the same message, then everybody who had a cell phone would go crazy. Normal people would see this, and the first thing they would do would be to call their friends and families on their cell phones. So the epidemic would spread like poison ivy. Then, later, I was walking down the street and I see some guy who is apparently a crazy person yelling to himself. And I want to cross the street to get away from him. Except he’s not a bum; he’s dressed in a suit. Then I see he’s got one of these plugs in his ear and he’s talking into his cell phone. And I thought to myself, I really want to write this story.

It was an instant concept. Then I read a lot about the cell phone business and started to look at the cell phone towers. So it’s a very current book, but it came out of a concern about the way we talk to each other today.

Then he doubles down on his warning to jump on those ideas when they’re still there in this interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books:

But for me, you reach a point of diminishing returns. Also, I’m older. I wrote more when I was younger, working on two different projects: I’d work on something new in the morning and something that was done at night. But it was never done to make money. It was done because all those ideas were there. They were all screaming to get out at the same time and they all seemed good.

Personally, I get my ideas from a demon baby that lives in my brain and tells me things by whispering them into my soul.

Y’know . . . like they do.

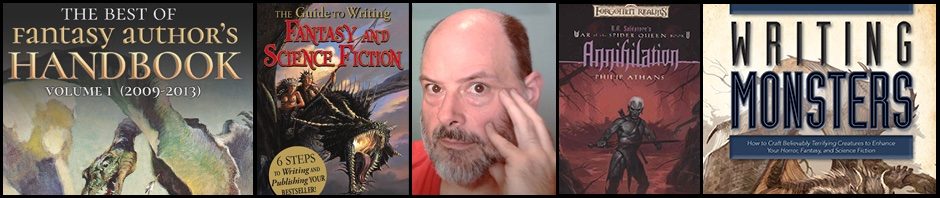

—Philip Athans

Great post, Phil! I love reading or hearing authors talk about the craft. In fact, even if I don’t read that particular author’s works, I love it. When my wife and I first moved here, I was a fish out of water and fell into a funk. Even though I suddenly had more time to write than I’d ever had before I couldn’t get in the mood – I had no ideas. My wife bought me the Masterclass with James Patterson. I’d never read any of his books (still haven’t), but just watching the videos and just listening to him talk about the sheer joy of writing and creativity got my batteries charging again. In truth, I probably read more writers’ books about their writing than I actually do their stories here lately. And Neil Gaiman and Stephen King are two of the best at this (present company excluded, of course).

Thanks for sharing. I certainly agree that daydreaming is the most important thing for getting ideas. I read an article some time ago that argued people are becoming less creative because we have no time to be bored. We are always connected. When we are waiting for something, we have our head in our phones, reading news or articles or whatever. But you need some time during the day when there is nothing to do but just think, to get lost in your head. Most of my ideas come to me either when I am in bed, or when I am driving in my car and listening to music. I am just too distracted during the rest of the day to think of irrelevant things.

I used to get the best ideas while out walking. I live in West Virginia, way up on top of a big mountain with bears and bobcats and all sorts of scary things, so a good walk around the mountain, or even to my mailbox (which is a mile round trip, I kid you not) gives me the perfect opportunity to run off steam, reflect on the day, plan things ahead, or create stories in my head as I look through the trees.

But, sometimes I don’t need a big, dramatic walk through the gravel roads. Sometimes I just get an idea at random. Random ideas are the scary ones because you may or may not remember what it was before you get a chance to write it down!

Pingback: Writing Links…9/18/17 – Where Genres Collide

Pingback: IT IS TO BE A BLOG POST ABOUT STARTING WITH A THEME | Fantasy Author's Handbook