We’ve come to the end of a five-part series inspired by H.P. Lovecraft’s essay “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction” in which one paragraph stood out for me as the beginnings of a horror/weird fantasy manifesto:

Each weird story—to speak more particularly of the horror type—seems to involve five definite elements: (a) some basic, underlying horror or abnormality—condition, entity, etc.—, (b) the general effects or bearings of the horror, (c) the mode of manifestation—object embodying the horror and phenomena observed—, (d) the types of fear-reaction pertaining to the horror, and (e) the specific effects of the horror in relation to the given set of conditions.

If you haven’t read the previous installments yet, here’s the link to part one. This week we’ll dig deeper into the fifth and final point:

(e) the specific effects of the horror in relation to the given set of conditions.

I’m taking this not as a second look at what it actually does, or what the “horror’s” powers are, but the larger effect it leaves on either or both of the characters and their world.

If this one weird thing has no lasting effect on anyone or anything it obviously wasn’t that big a deal in the first place. Of course, the exact parameters of that “lasting effect” can come in any form and can be attached to just a single person or the entire universe—or anywhere in-between.

Good stories—strong plots, anyway—depend on establishing what’s at stake and increasing the stakes as the story develops. And that’s really what we’re talking about here in terms of our “one weird thing”: What’s at stake?

Donald Maass devoted a whole chapter of his highly recommended book Writing the Breakout Novel to “stakes”—as in: What’s at stake? This is an essential question not just for each story but for each scene within, and Maass breaks it into two categories: Public Stakes and Personal Stakes.

Public Stakes go to the effect of the one weird thing on the whole world, or anyway some community of people:

A larger significance can be attached to the outcome of just about any story. It is a matter of drawing deeper from the wells at hand, particularly the story’s milieu. For instance, every setting has a history—and what is history if not a chronicle of conflicting interests? Every protagonist has a profession—and what profession lacks ethical dilemmas?

If you want to establish a character’s goal as: I have to stop the one weird thing from fully manifesting on Earth! That has to be followed by a good answer to the question: Or what?

What bad thing will happen if the one weird thing fully manifests on Earth?

If you haven’t seen the movie The Cabin in the Woods, you really ought to. I think it’s a great example of a story that establishes a high stakes environment for its characters—but not the set of characters we think we’re actually rooting for, the young people who rent the cabin. Instead it’s the two guys in the weird underground office complex that actually understand the consequences—have a real grasp on what’s at stake if their undead hillbillies fail in their mission of murder. This is only broadly hinted at at first but we see by their reactions and the reactions of the people around them that as scary as things are out in that cabin in the woods, the consequences for all of humanity are much, much higher.

What do I miss about working at Wizards of the Coast? I’ve actually been in meetings with white boards that look like this!

Drew Goddard and Joss Whedon do this by making us like these guys. We get them, and as creepy and murderous as their jobs are, we start to understand that they’re not bad guys but good guys in a horrific situation. The Cabin in the Woods communicates what’s a stake by “creating high human worth,” as Donald Maass advises in his book. And bonus points that we see (spoiler alert) those consequences play out, or at least begin to, at the very end.

This actually combines the Public Stakes of the impending apocalypse with the Personal Stakes of these two poor saps being our last line of defense, and failing.

Combining Public and Personal Stakes again, a character can perform some sacrifice in order to save someone he loves, or even save the whole world from something no one else even knows was ever a threat, as we saw attempted in The Cabin in the Woods and eighty-four years earlier in the final paragraph of H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu”:

Cthulhu still lives, too, I suppose, again in that chasm of stone which has shielded him since the sun was young. His accursed city is sunken once more, for the Vigilant sailed over the spot after the April storm; but his ministers on earth still bellow and prance and slay around idol-capped monoliths in lonely places. He must have been trapped by the sinking whilst within his black abyss, or else the world would by now be screaming with fright and frenzy. Who knows the end? What has risen may sink, and what has sunk may rise. Loathsomeness waits and dreams in the deep, and decay spreads over the tottering cities of men. A time will come—but I must not and cannot think! Let me pray that, if I do not survive this manuscript, my executors may put caution before audacity and see that it meets no other eye.

This leaves the threat of the one weird thing still hanging—the stakes left still high. Our hero managed to escape the worst of it, saving the world in the process, but next time maybe we won’t be so lucky.

Lovecraft wrote “The Call of Cthulhu” in 1926 and it was first published about a year and a half later, but looking at that story again it had me thinking about nuclear weapons.

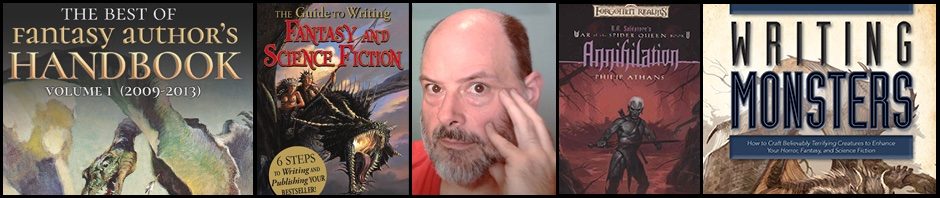

There’s one weird thing that was still almost twenty years in Lovecraft’s future, but has a similar vibe. In Writing Monsters I looked at the indelible link between the atomic bomb and Godzilla, and it’s interesting to see the idea of the threat to the world constantly hanging over our heads predating the reality. But I suppose this goes back to Armageddon and various mythical world-ending catastrophes. I can image the first cave man to ride out an earthquake thinking, Is that going to happen again? He was the progenitor of the apocalyptic vision.

But even if there are no Public Stakes, per se, at least the fate of the world doesn’t hang in the balance in your story—and it doesn’t have to!—you still have to focus on the Personal Stakes.

Starting with a single person, the effect of the weird thing on that character can be any combination of positive and negative. It could be that defeating the evil thing provides the character with some redemption or feeling of satisfaction. That’s more or less standard in both science fiction and fantasy but actually pretty rare in a horror story, which more often ends like this, from Stephen King’s short story “Nona”:

I’m going to kill myself now. It will be much better. I’m tired of all the guilt and agony and bad dreams, and also I don’t like the noises in the walls. Anybody could be in there. Or anything.

Here we see one hapless “hero” paying the price for his encounter with weirdness, a fate shared by many of Lovecraft’s own characters. The one weird thing may not kill you, but you may end up wishing it had.

Either way, the key component is that your one weird thing is actually interesting enough to justify its existence—to justify the existence of the story itself. As H.P. Lovecraft himself said in the same article that inspired this series:

Being the principal thing in the story, its mere existence should overshadow the characters and events. But the characters and events must be consistent and natural except where they touch the single marvel. In relation to the central wonder, the characters should shew the same overwhelming emotion which similar characters would shew toward such a wonder in real life. Never have a wonder taken for granted. Even when the characters are supposed to be accustomed to the wonder I try to weave an air of awe and impressiveness corresponding to what the reader should feel. A casual style ruins any serious fantasy.

Make sure that your one weird thing actually matters!

—Philip Athans

Pingback: LOVECRAFT’S FIVE DEFINITE ELEMENTS, PART 4: WHAT MAKES IT SCARY | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Pingback: HORROR AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK—THE HALLOWEEN EDITION | Fantasy Author's Handbook