Choosing to be isolated from others is a trait we don’t routinely recognize as healthy. Worse, we often see it as either the result of a dangerous psychological imbalance or the cause of a dangerous psychological imbalance. This is true in reality as much as in fiction.

In “For 40 Years, This Russian Family Was Cut Off From All Human Contact, Unaware of World War II” Mike Dash wrote for Smithsonian.com:

The four scientists sent into the district to prospect for iron ore were told about the pilots’ sighting, and it perplexed and worried them. “It’s less dangerous,” the writer Vasily Peskov notes of this part of the taiga, “to run across a wild animal than a stranger,” and rather than wait at their own temporary base, 10 miles away, the scientists decided to investigate. Led by a geologist named Galina Pismenskaya, they “chose a fine day and put gifts in our packs for our prospective friends”—though, just to be sure, she recalled, “I did check the pistol that hung at my side.”

It’s not unusual to see isolation as a theme popping up in “weird” fiction, mostly horror, though I’ve found two good examples of science fiction authors isolating their characters from the outside world, and for very different reasons. The most recent is Joe M. McDermott’s The Fortress at the End of Time in which characters are essentially imprisoned, or more or less exiled, to the farthest reaches of space to watch for an enemy no one seems to believe is ever coming. This plays into a very old military tradition in which younger or “problem” soldiers are “reassigned” to the worst duty possible—the most isolated places:

The ansible rings true and through it all. The planet called Citadel is the farthest colony of man from Earth. The station called Citadel placed herself above the only desert rock they had in range with enough magnetic fields to sustain a planetary colony against the stellar winds. They gathered ice comets and liquid moons and hurled them upon the surface to inject life into the ground before the damaged battleship’s supply ran out, but it is not enough to sustain a complex economy like Earth’s. It is described as a desert in its lushest places, a wind-blasted moonscape where man has not begun to change the ground. Terraforming is always slow, and as distant as they are relative to the center of cosmic gravity, the speed of terraforming seems even slower to the solar system. Every year, Earth is three weeks faster than us on the Citadel. It is Sisyphean to consider a place like this, and it is Sisyphean to sit here in my little cell and write about what is obvious to everyone: This is a terrible posting at the edge of human space and time, and everyone here knows it, even you.

But not everyone is necessarily sent to the hinterlands as punishment. Some people choose to go there, like the Arctic researchers of the science fiction classic “Who Goes There?” by John W. Campbell, which was originally published in Astounding Science-Fiction in 1938 under the pseudonym Don A. Stuart, and has since been made into at least three movies called The Thing. See how Campbell casts the environment as a second, even worse monster:

Drift—a drift-wind was sweeping by overhead. Right now the snow picked up by the mumbling wind fled in level, blinding lines across the face of the buried camp. If a man stepped out of the tunnels that connected each of the camp buildings beneath the surface, he’d be lost in ten paces. Out there, the slim, black finger of the radio mast lifted 300 feet into the air, and at its peak was the clear night sky. A sky of thin, whining wind rushing steadily from beyond to another beyond under the licking, curling mantle of the aurora. And off north, the horizon flamed with queer, angry colors of the midnight twilight. That was spring 300 feet above Antarctica.

At the surface—it was white death. Death of a needle-fingered cold driven before the wind, sucking heat from any warm thing. Cold—and white mist of endless, everlasting drift, the fine, fine particles of licking snow that obscured all things.

Kinner, the little, scar-faced cook, winced. Five days ago he had stepped out to the surface to reach a cache of frozen beef. He had reached it, started back—and the drift-wind leapt out of the south. Cold, white death that streamed across the ground blinded him in twenty seconds. He stumbled on wildly in circles. It was half an hour before rope-guided men from below found him in the impenetrable murk.

It was easy for man—or ‘thing’—to get lost in ten paces.

This is where we really see the story utility of characters in isolation. If, say, an alien monster attacks and the first thing everybody does is dial 911, the police show up, then the National Guard, then the Army . . . well, that’s a very different story. And though there have been stories that have gone that route, what things like the various versions of Godzilla end up lacking is a strong protagonist. Once the Army comes in, it’s tough to focus all efforts on one person, and show how a single hero can take responsibility for solving this monster problem, like McReady does in “Who Goes There?” or Ripley does in Alien—both much more satisfying stories.

Sometimes, as we hit on last week looking at Lovecraft’s “Five Definite Elements” of a weird tale, it’s about isolating a group of people so we can bring out not just the heroic in the hero, but the villainous in the villain.

I adore this chilling little interchange from the horror classic The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson:

“I leave before dark comes,” Mrs. Dudley went on.

“No one can hear you if you scream in the night,” Eleanor told Theodora. She realized that she was clutching at the doorknob and, under Theodora’s quizzical eye, unclenched her fingers and walked steadily across the room. “We’ll have to find some way of opening these windows,” she said.

“So there won’t be anyone around if you need help,” Mrs. Dudley said. “We couldn’t hear you, even in the night. No one could.”

“All right now?” Theodora asked, and Eleanor nodded.

“No one lives any nearer than the town. No one else will come any nearer than that.”

“You’re probably just hungry,” Theodora said. “And I’m starved myself.” She set her suitcase on the bed and slipped off her shoes. “Nothing,” she said, “upsets me more than being hungry; I snarl and snap and burst into tears.” She lifted a pair of softly tailored slacks out of the suitcase.

“In the night,” Mrs. Dudley said. She smiled. “In the dark,” she said, and closed the door behind her.

The Haunting of Hill House isolates a small group of characters in a haunted house and though none of them emerge as a “villain,” per se, the story is about what each of them brings to that haunting—adding their own metaphorical “ghosts” to the disembodied population of Hill House.

We all know that the confidence that someone will come to help gives people at least a bit of extra courage. In fact, our whole society pretty much depends on that. We cluster together as tribes, establish cities, so we have neighbors we can call out to for help. When that fails us we tend to go a little nuts. You’ve probably heard of the infamous case of Kitty Genovese, a young woman murdered on a Queens, New York street while her neighbors supposedly listened and even watched, but never tried to help or even call the police. Turns out that lack of response was more urban legend than urban isolation (I’ll refer you to the documentary The Witness for the real story), but that sense of the horror of isolation remains.

Remember the tag line: In space, no one can hear you scream?

Some stories go to the final step, isolating one single character. In Harlan Ellison’s 1956 short story “Life Hutch,” a lone astronaut is trapped in a shelter on a remote asteroid—with a malfunctioning robot that will kill him if he moves. It’s a personal favorite of mine, as is Stephen King’s story “Survivor Type” from the collection Skeleton Crew, which begins with:

January 26

Two days since the storm washed me up. I paced the island off just this morning. Some island! It is 190 paces wide at its thickest point, and 267 paces long from tip to tip.

So far as I can tell, there is nothing on it to eat.

From there the story is as much a fictional memoir as it is a particularly disturbing work of “body horror.” What Dr. Richard Pine finally resolves to do to feed himself makes for King’s most disturbing story ever, and utterly and completely relies on isolation.

Humans are pack animals. We need each other, even if we sometimes turn on each other, so when you want to scare your readers, put them in a tight space alone or with just a few other people. And then, maybe, The Hills Have Eyes-fashion, throw at them villains who are really isolated, like that poor Russian family.

Not that they were villains at all, but . . . victims?

From that Smithsonian article: “What amazed him most of all,” Peskov recorded, “was a transparent cellophane package. ‘Lord, what have they thought up—it is glass, but it crumples!’ ”

—Philip Athans

Did this post make you want to Buy Me A Coffee…

Follow me on Twitter @PhilAthans…

Link up with me on LinkedIn…

Friend me on GoodReads…

Find me at PublishersMarketplace…

Check out my eBay store…

Or contact me for editing, coaching, ghostwriting, and more at Athans & Associates Creative Consulting?

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

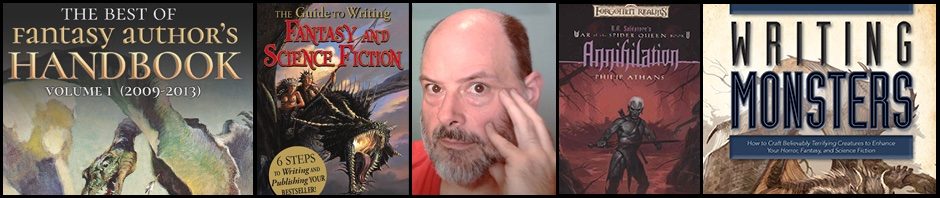

Editor and author Philip Athans offers hands on advice for authors of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and fiction in general in this collection of 58 revised and expanded essays from the first five years of his long-running weekly blog, Fantasy Author’s Handbook.

Pingback: Writing Links…3/13/17 – Where Genres Collide

Hey, I nominated you for the Blogger Recognition Award. Keep up the great work! http://redstringpapercuts.com/2017/03/14/blogger-recognition-award/

Pingback: HORROR AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK—THE HALLOWEEN EDITION | Fantasy Author's Handbook