It’s funny how sometimes these blog posts just pop up right in the moment.

This morning, while working through this week’s session of my online Worldbuilding course, commenting on one of the students’ assignment describing a monster, I paraphrased an interview with filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock that I remembered from college. That was a long tome ago and in my mind I swapped his words “surprise” and “suspense” with “horror” and “terror”—but the sentiment is the same.

God forbid I Google the thing before quoting it, but anyway I Googled at after I quoted it and found this, via the Olympia (Washington) High School of all places:

Mystery, Surprise, and Suspense According to Alfred Hitchcock

The following is an interview between famed French director Francois Truffaut (F.T.) and Alfred Hitchcock (A.H.).

F.T.—The word suspense can be interpreted in several ways. In your interviews you have frequently pointed out the difference between mystery, surprise, and suspense. Many people are under the impression that suspense is related to fear.

A.H.—There is no relation whatever. Let’s go back to the switchboard operator in Easy Virtue an early Hitchcock film. She is tuned in to the conversation between the young man and the young woman who are discussing marriage and who are not shown on the screen. That switchboard operator is in suspense; she is filled with it. Is the woman on the end of the line going to marry the man whom she called? The switchboard operator is very relieved when the woman finally agrees; her own suspense is over. This is an example of suspense that is not related to fear.

F.T.—Yet the switchboard operator was afraid that the woman would refuse to marry the young man, but, of course, there is no anguish in this kind of fear. Suspense, I take it, is the stretching out of an anticipation.

A.H.—In the usual form of suspense it is indispensable that the public be made aware of all the facts involved. Otherwise, there is no suspense.

F.T.—No doubt, but isn’t it possible to have suspense in connection with hidden danger as well?

A.H.—To my way of thinking, mystery is seldom suspenseful. In a whodunit, for instance, there is no suspense, but a sort of intellectual puzzle. The whodunit generates the kind of curiosity that is void of emotion, and emotion is an essential ingredient of suspense.

In the case of the switchboard operator in Easy Virtue, the emotion was her wish that the young man be accepted by the woman. In the classical situation of a bombing, it’s fear for someone’s safety. And that fear depends upon the intensity of the public’s identification with the person who is in danger.

I might go further and say that with the old situation of a bombing properly presented, you might have a group of gangsters sitting around a table, a group of villains . . .

F.T.—As for instance the bomb that was concealed in a briefcase in the July 20 plot on Hitler’s life.

A.H.—Yes. And even in that case I don’t think the public would say, “Oh, good, they’re all going to be blown to bits,” but rather, they’ll be thinking, “Watch out. There’s a bomb!” What it means is that the apprehension of the bomb is more powerful than the feelings of sympathy or dislike for the characters involved. And you would be mistaken in thinking that this is due to the fact that the bomb is an especially frightening object. Let’s take another example. A curious person goes into somebody else’s room and begins to search through the drawers. Now you show the person who lives in that room coming up the stairs. Then you go back to the person who is searching, and the public feels like warning him, “Be careful, watch out, someone’s coming up the stairs.” Therefore, even if the snooper is not a likable character, the audience will still feel anxiety for him. Of course, when the character is attractive, as for instance Grace Kelly in Rear Window, the public’s emotion is greatly intensified.

As a matter of fact, I happened to be sitting next to Joseph Cotten’s wife at the premiere of Rear Window, and during the scene where Grace Kelly is going through the killer’s room and he appears in the hall, she was so upset that she turned to her husband and whispered, “Do something, do something!”

F.T.—I’d like to have your definition of the difference between suspense and surprise.

A.H.—There is a distinct difference between suspense and surprise and yet many pictures continually confuse the two. I’ll explain what I mean. We are now having an innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens and then all of a sudden, “boom!” there is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence.

Now let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the décor. The public can see that it is quarter to one. In these conditions the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen, “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb beneath you and it’s about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is, in itself, the highlight of the story.

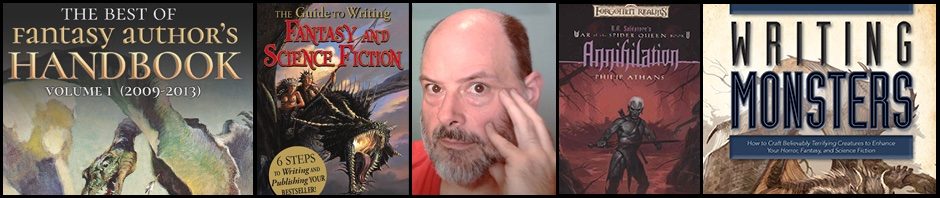

In that reply to a student this morning I paraphrased a portion of this interview in regards to the introduction of a monster into a story. In Writing Monsters, I went into some length regarding the staging of the reveal of a monster, working under what I continue to defend is an accurate premise: The more we know about a monster the less scary it becomes.

I think this is mostly true, but what about the other possibility, that the more you know of a monster the scarier it becomes?

Consider The Walking Dead.

Even before that series started, we knew what the George Romero-style zombie can and can’t do, and we know how to kill it. The Walking Dead chose not to mix that up in any detectable way, so here we have slow moving, dim-witted cannibals than can only be killed by traumatic brain injury.

Check.

But that doesn’t make them any less scary. In fact, knowing that they’re offering the Death of a Thousand Bites makes them scary. Knowing that they can be killed but it isn’t easy makes them even scarier. Putting a whole horde of them together to overwhelm you makes them scarier still.

So what The Walking Dead and similar monster stories play off of isn’t the sense of mysterious “other” that many, if not most monster stories depend on, but the terror of knowing precisely how bad it’s going to be if they get you in their clutches—and that can be sustained for a lot longer. They can, conceivably, remain scary episode after episode, season after season, because we know there’s a bomb there, essentially, and know that it can go off any minute, and knowing what a bomb can and can’t do or that under some set of limited circumstances it could be defused, doesn’t necessarily lessen that suspense, that terror.

—Philip Athans

This just in: If you have HBO you must watch the documentary, just added: Hitchcock/Truffaut. Why have I not read this book yet? I’m going to!

Pingback: LOVECRAFT’S FIVE DEFINITE ELEMENTS, PART 4: WHAT MAKES IT SCARY | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Pingback: WHOSE POV SHOULD IT BE? | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Pingback: FIRST, SECOND, OR THIRD… PERSON, THAT IS | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Pingback: HORROR AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK—THE HALLOWEEN EDITION | Fantasy Author's Handbook