As part of the process of writing The Guide to Writing Fantasy & Science Fiction, I interviewed a few key players in the SF/fantasy community. Their wisdom and generosity is liberally sprinkled throughout the book, but I couldn’t use every word—and wanted to do some follow-ups. What follows is an expanded interview with best-selling science fiction and fantasy author Paul Park.

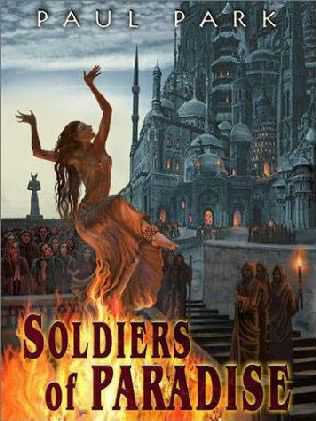

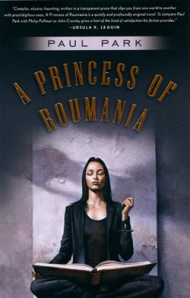

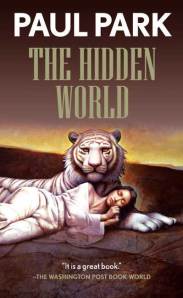

Paul Park first came to the attention of the science fiction and fantasy community with the 1987 publication of Soldiers of Paradise, the first of the Starbridge Chronicles books. A prolific and critically-acclaimed author of short stories, brought together in the 2002 collection If Lions Could Speak, Paul Park blew the critical community away five years ago with the fantasy novel A Princess of Roumania, which was soon followed by its sequels, The Tourmaline, The White Tyger, and The Hidden World. He teaches at Williams College in Massachusetts.

Philip Athans: Please define “fantasy” in 25 words or less.

Paul Park: In fantasy stories, the archetypes and myths that form the subtext of much ordinary fiction are brought to the surface and made real.

Athans: Please define “science fiction” in 25 words or less.

Park: You write science fiction for a community of readers. If they accept it, that’s what it is. Context is more important that treatment or content.

Athans: When you first started writing, where did you go to learn your craft? Did you consult books like The Guide to Writing Fantasy & Science Fiction? Did you pursue a degree with writing in mind?

Park: I did everything wrong. This is partly because I had no sense of the community; at a certain point I was shocked to learn, for example, that Kim Stanley Robinson and Ursula K. LeGuin actually knew each other. When I wrote Soldiers of Paradise, my first book, I didn’t realize I was working in the context of a genre, a tradition of literature much larger than the one or two classic texts I’d read. Creatively that’s okay, or partially okay, because you can drive yourself crazy with too much knowledge. The downside is, when you publish a genre book, it’s as if you are breaking into a conversation between writers and readers that is already going on, and if you don’t know anything, you think your own ideas are new just because you haven’t heard them before. I remember being surprised, when the reviews of my first book came out, to hear it dismissed in some quarters as an imitation of Gene Wolfe, or else of Brian Aldiss, brilliant writers whom I hadn’t yet read. A little knowledge would have helped me there.

As for learning my craft, I didn’t take any creative writing classes, or read any books—again, I wish I had. I was arrogant when I was younger, and didn’t think I could learn anything from anyone else’s experience. This is a mistake. On the other hand, arrogance can sustain you when nothing else does.

I do some teaching now, at Clarion and at Williams College, and I’ve come to believe in its utility—I’ve seen too many people improve. Good teachers, whether books or people, can oblige you to look at problems from the outside, and require you to bring the solutions up from the level of instinct to the level of conscious thought. You start to be a good writer when you can achieve some distance from your work, when you can hold it at arm’s length and examine it for flaws. Teachers help you with that.

Athans: What advice can you give an aspiring fantasy author on how to approach the creation of fantasy customs and social structures? Is there such a thing as too much detail?

Park: Most fantasy landscapes are nostalgic in nature, dependent on a shared sense of history or myth. The interesting landscapes are familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. The trick is to make them familiar enough to evoke and resonate with an entire tradition, while unfamiliar enough to resist melting into other, more primary texts. An accumulation of specific detail is how you accomplish this, and while there might be limits on what you can cram into the actual story, there are no limits on what it would behoove you to imagine.

Athans: How do you approach the creation of new languages, or variations on existing languages, so your worlds have their own idiom, colloquialisms, etc.?

Park: Good question. I shy away from invented vocabulary, which tends to sound bogus to me. It only works if you take the trouble to invent an entire language, as Tolkien did. Otherwise, you’re better off working on the level of speech rhythms, rather than individual words—anapests versus dactyls, that sort of thing.

Athans: How did you approach the creation of a magic system for A Princess of Roumania? Do you research historical occult practices, start with a clean slate, or some combination of both?

Park: I did a certain amount of research into the history and technology of alchemy, and then imagined that alchemy actually worked. The magical procedures in the books were derived from scientific procedures.

Well, perhaps I should have said “scientific” procedures, since the alchemists were wrong about most things. But for example, many of them were interested in communing with the spirits of the dead, and interested also in the idea that in a geo-centric universe, the world was wrapped in spheres, each one with a spiritual or metaphysical meaning. In the book, the Baroness Ceausescu has access to a type of technology that enables her to communicate to her dead husband, through a device rather like a gramophone.

Or else they were interested in scrying glasses of different kinds, in which they were able to see and even influence events as they transpired, at a distance—not directly, but in a language of metaphor. The baroness has various devices of this type, which she is constantly misinterpreting.

Many were interested in memory palaces, or else conscious and painstaking mental creations through which they could not only make sense of, but actually influence the world. The Elector of Ratisbon, because of a combination of arrogance and rigorous training, is able to create entire landscapes in his mind, which then with an effort of will he can superimpose on actual landscapes, altering them.

Athans: What is the most important element to a richly-realized character (his back-story, goals, politics/morality/ethics, family/relationships)? Where should an author start?

Park: I often start by imagining the character as a physical and psychological object, and then imagining how that object appears to other people in the drama, including me. Then I start adding detail to justify or confound those assumptions. Then I go deeper, to see if I can discover an interior landscape that challenges the exterior one—in other words, how the character appears to him or herself. Then I invent a personal or family or romantic history that explains, or at least resonates with, those differences. Character motivation derives out of that process; it’s not what I start with. But if everyone in the story knows the same things about a character, or imagines him or her in the same way as the author does, and there’s no gap between what the character perceives and what the reader perceives, there’s usually a problem.

Athans: How do you keep fantasy, a very old genre, fresh? How do you avoid clichés and balance traditional fantasy archetypes with new concepts?

Park: I’d advise beginners to avoid swords, horses, castles, battles, and the problems of the aristocracy. It takes a very skilled writer to handle that stuff. Everyone else, you might consider putting the traditional fantastical elements into the relationships between the characters, rather than the hardware.

Athans: How much effort and research goes in, before you actually start writing, to establishing the available technology, either futuristic, fantastical, or historical?

Park: Research can be a trap, a way to delay starting a book. I don’t do a whole lot of general research; it’s mostly on a need-to-know basis. After all, it’s what you invent that will make your book original or derivative, and you can get started on that anytime.

Athans: What’s more difficult, getting your first book published, or maintaining a career after that debut?

Park: Maintaining a career is harder, I think. People love new writers.

Athans: What have you found to be the most surprising aspect of being a professional, published author—what were you least prepared for when you were still “aspiring”?

Park: I guess I was unprepared for how nice everyone was, and how supportive. Writing is one of the loneliest of trades. But the publishing community is welcoming and warm. This is particularly true in the genres, because our work, no matter how brilliant, tends to be discounted in the outside world. This gives us an appealing humility, I think.

I think so, too. Thanks, Paul.

—Philip Athans

Pingback: Paul Boccaccio › Characterized Through Stereoscopy

Pingback: STEP THREE ERRATA & ADDITIONAL MATERIAL: The Guide to Writing Fantasy and Science Fiction (PART 1) | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Pingback: THE FANTASY AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK INTERVIEWS | Fantasy Author's Handbook