A Short Story by Philip Athans

He’d been awake for at least an hour before the alarm clock started beeping. Still, he paused before reaching over to turn it off. With a sigh he rolled onto his back and glanced over to his left. He made eye contact with his wife, but only briefly, and knew it would be the only time their eyes would meet that day.

She rose first, sliding from the sheets without a sound, and tiptoeing out of the bedroom on stiff legs. He sat up a few seconds after she’d left the room and spent a few more seconds staring at the dark, empty doorway after her. It was still dark in the bedroom, the sky behind the blinds revealed the first glow of the approaching sunrise filtering through the tall and shabby fir trees that lined the edges of the back yard. He looked at the clock, 6:03 am, and stretched. Little pains traced the tired muscles of his back, neck, and shoulders, then moved to his thighs, knees, and ankles as he stood. He ignored them—signs of age, he guessed. It didn’t matter.

He went to the bathroom and closed his eyes then flipped the lights on. He hated the hot color of the halogen lamps, and every morning thought he should have someone come in and install a softer light fixture—and every day he forgot all about it. He blinked a couple times to let his eyes adjust to the light, and passed the mirror to the toilet without looking at himself.

He urinated, the sound of it mixing with the grumbling roar of the coffee grinder from downstairs. When he was done he flushed the toilet and stepped to the sink, letting it run a minute before washing his hands. Shaving was best done as quickly as possible, and he’d perfected the process without having to make eye contact with himself in the mirror. He looked at his chin, at his neck, at his upper lip, but not his own eyes or the dark circles under them. He spent as little time as possible in front of mirrors.

While he drained the sink he watched the little whiskers swirl down the drain and thought about exercising. He knew he should—he wasn’t getting any younger or thinner—but he didn’t want to. He didn’t like working out, though it did make him feel a little better, a little more energetic, a little less prone to bouts of suicidal depression. Still, he knew he could be as suicidally depressed as he wanted, but could never kill himself, he didn’t really want to be any more energetic than he absolutely had to be, and all that left was being a little bit healthier, living a little bit longer.

Wondering if deciding to let himself go counted as suicide, after all, he turned on the shower without exercising.

Not having to worry about how much water he used, he stayed in the shower as long as he could, mostly just standing there, letting the hot water pour over himself as he traced the veins in the expensive Italian marble with a lazy eye. He touched the handle for the steam a few times, but never turned it on. He wasn’t sure he liked the steam, he’d just bought it because it was more expensive, and maybe his wife had mentioned liking it, but he couldn’t remember.

The rest of his morning routine passed they way it did most days, without him thinking about it. His favorite part of the morning, which tended to be his favorite part of the day, was the fact that he didn’t have to think. He stepped into the closet, and had a passing recognition, again, that it was too big. But his wife had asked for big closets, and big closets were provided.

His clothes took up less than a tenth of the space. Hers, most never worn, filled the rest in a dizzying array of colors. He had a few casual shirts, but mostly suits, alternating black and gray, the only two colors that had been deemed acceptable. He chose a gray one and put it on quickly, having noticed that he’d spent just a little too much time in the shower.

When he left the bedroom—leaving the bed unmade, his dirty clothes on the floor of the closet, and wet towels on the floor of the bedroom—his daughter’s door, across the wide upstairs hall, opened a crack but quickly shut. She must have just gotten out of bed, but before she could make it to the bathroom had seen or heard him. He didn’t let himself look at the closed door as he passed, but walked to his son’s room instead. His door was slightly ajar and when he pushed it open the hinges squeaked, startling him.

“Time to get up, buddy,” he said. His son turned in his bed and looked up at him. He didn’t say anything, but by the look in his eyes, it was apparent he’d been awake for hours.

“Okay, Dad,” he said, his voice flat, not tired, empty.

He nodded and turned away, closing his son’s door behind him. He closed his eyes and rubbed his face with both hands, trying to shake the image of his son‘s eyes, and the sound of his son’s voice, from his mind.

“Don’t,” he whispered to himself, but only thought, think.

He went downstairs, forcing himself not to hurry though he wanted coffee and wanted it badly, especially when the smell wafted up from the kitchen. The lights in there were a little softer, a little more inviting. His wife had already poured herself a cup. She sat on a stool at the granite-topped island, sipping coffee from a dainty little china cup she had bought from some antique dealer at Pike Place Market. Without wanting to suffer over the memory, he realized it was the last time they’d been there, just after he started practicing law, when his daughter was still a baby. Before everything changed. She only ever drank coffee out of that cup and though he wondered why, he never asked her.

“Good morning,” she said. “Are the kids up?”

He nodded, even though she never looked up at him, and he poured himself a cup of coffee. He sat at the kitchen table, in a chair facing away from his wife, and took a sip of the coffee. It was too hot and burned his lower lip, but he didn’t care.

“I’m thinking about taking the early ferry,” he said.

She didn’t respond, but he didn’t expect her to.

“I’ll be home at normal time, though,” he said.

“I’ll make the chicken you like,” she said, and though he couldn’t see her, he could tell by the sound of her voice that she wasn’t looking at him.

Though he wondered what chicken she was talking about, he didn’t ask. He finished his coffee too fast, ignoring the pain in favor of the caffeine, then hurried to leave. He knew his daughter didn’t like to come downstairs in the morning if he was still there, and he didn’t want to make her late for school, regardless of the fact that the school would never complain, would let her come and go as she pleased.

He picked up his briefcase, still sitting just inside the front door, untouched, unopened, since the night before. He never worked at home, but felt like he should keep up appearances so he carried it back and forth every day. The papers inside were old, irrelevant, just there to give the thing some heft.

He opened the too-wide front door and stepped out onto the porch. The early autumn air was cool, and a light fog permeated the trees that lined the driveway. The driver turned on the headlights when he crossed the porch, and he winced at the sudden light. The driver must have seen him. The headlights went off. The car ground to a halt, a long black limousine polished to a mirrorlike shine.

He hated the car. He loathed the sight, the very thought of it. But it was his—it was provided for him, anyway. He wasn’t sure he owned anything, but all the best things were made available to him, provided for him, lent for his comfort and convenience. He wasn’t meant to think about such mundane matters as cars and houses, wasn’t expected to do for himself.

It had taken him more than two months to train the driver not to step out of the car and open the door for him. The terror in the man’s eyes at the thought of the break in protocol almost made him give up, but ultimately he won out, and the driver stayed at the wheel while he opened the door and climbed in all on his own.

The woman waiting for him that morning was Asian, maybe Thai or Vietnamese. He’d never seen her before, or at least didn’t remember her. She wasn’t tall but looked like she was—thin, her face long and her lips full. She wore a black knit sweater, too light for the cool morning air, with a white tank top under it, and black slacks. Not an overtly alluring outfit, but he had made it known over time that he didn’t like them the way some of his colleagues did, so they started to come more understated.

He only really glanced at her face, just long enough to register the fear in her eyes, fear mixed with anticipation. He looked out the window, ignoring her as the car pulled away from his house.

The structure always looked different to him somehow, every time he looked at it, as though it changed every night so that he pulled away from a different house every morning. That wasn’t in fact true, of course, but still he couldn’t register the house as his, as “home.”

Technically speaking, of course, the house wasn’t his, any more than the car was, his suit was, his watch was, or the woman was.

“Good morning,” the girl said, and he liked the sound of her voice. It didn’t shake much, like most of the girls’ did. “Can I . . .?”

He wondered whether she didn’t finish the sentence because she didn’t want to, or on purpose. She might have thought he’d want to finish the sentence himself. Anyway, they both knew why she was there.

He shook his head and he could hear her settle back into the leather seat. He stared out the window hoping she wouldn’t try to talk to him, but as the ride progressed, and she remained silent, he snuck a few wary glances her way.

She was beautiful. Any man would have . . .

He wouldn’t think about it. He wouldn’t remember the other girls, the mornings or afternoons when he’d let himself . . .

For the rest of the ride to the ferry he tried not to think about all the things he’d taken, all the while telling himself he shouldn’t be taking it, didn’t want it, didn’t deserve it when so many . . .

Once they got on I-90 west toward Seattle it was only about twenty minutes in the restricted lane to the ferry terminal. A policeman with a red flashlight beckoned them into another restricted lane. No one in any of the cars they passed, people waiting for other ferries, looked up as they passed, even when he tried to make eye contact with them. They wouldn’t be able to see him through the tinted windows, anyway, but some mornings he felt he had to try.

The Asian girl started to fidget the moment they’d entered the ferry terminal. Why wouldn’t she?

“You’re sure you . . . ?” she tried again. He could easily detect the hopeful note in her voice—the hope that he would say no again.

A small part of him, a part of him that made his jaws tense, wanted to spend the second half of his commute fucking her—her skin he could tell even from a yard away was soft as silk, her lips even softer. He knew how good she would feel, knew as well that she would do whatever he asked of her—give what he took from her without question or hesitation. And all the while she would be choking back bile, desperate not to throw up until she was free of him.

He shook his head without looking at her. When the car paused while the special ferry eased its way against the dock, he said, “You can get out here.”

“Did I do something wrong?” she asked, panic coloring her voice in shades of red.

“No,” he said, looking at her—at her breasts, small and perfectly round, not her eyes. “I just . . .”

She reached for the door handle, a fast jerk forward that embarrassed, or scared, her. She stopped before opening the door. “You’re sure, I—”

“You’re fine,” he said, looking away.

She hesitated just long enough to let him know she wanted more, wanted some reassurance that she had not displeased him, that she would not be punished, but he couldn’t help her with that. He only vaguely remembered a world in which anyone could make assurances. She opened the door and got out of the car. The door slammed shut and they pulled onto the ferry. He turned to watch her go, admiring her again—she was beautiful—and taking no offense at the way she tried to walk as fast as she could without running.

Another half an hour on the ferry, and he sat in the car, like he always did—or almost always. There were days he would leave the car and stand at the rail, breathing the clean salty air of the Sound. But those days had grown increasingly infrequent. The smell had gotten worse, so that on the best day it was barely better than intolerable.

He looked at his briefcase and had a fleeting thought that he should have brought something to read, something to occupy his mind. He remembered reading—he used to like reading—but couldn’t quite pin down the last time he’d read a book. The sound of his cell phone startled him, and he took a deep breath before answering it.

“You’re almost here,” his assistant said. It wasn’t a question.

He nodded before realizing she couldn’t see him, but before he could say anything she said, “A meeting has been called.”

He paused.

“Jason Wendly has called a meeting,” she said.

His breath caught but he managed to respond, “When?”

“They’ll be waiting for you.”

“So early? Did Kathy say anything?” he asked, the blood running cold in his veins. He actually shivered.

“No.”

“Her assistant?” he asked. “Anyone?”

“No, sir,” his assistant said.

He stopped to think, but his mind was blank. He had to remember to breathe, and force a breath past a tight chest, down a dry throat.

“You’re on your way,” she said, and he winced at the cold desperation in her voice.

He nodded then slid the phone closed, cutting off the connection just as the ferry jerked gently in the water, shedding speed as it approached the entrance. The morning had proved to be gray, but not too dark. A thin, high marine layer made the water around them battleship gray.

The diffuse sunlight faded as the ferry was enveloped in the darkness of the tunnel. His hands shook as the light, the heat, the very life seemed drawn out of the air around him. He closed his hands into sweaty, stiff-fingered fists and they stopped shaking. It took five minutes for the ferry to crawl from the tunnel entrance to the dock, and the car started a second before the gentle forward lurch of the ferry touching the dock then drove off onto the main lot.

He breathed a few times in through his nose, out his mouth, and steadied himself so that when the car pulled up to the main entrance and he was reasonably sure he would appear calm. He waited for the driver to get out and open the door for him. At home, that was one thing, but at work—the driver didn’t deserve what would have happened to him if he hadn’t.

Four people he only vaguely recognized stood in a little cluster around the door, talking in excited, jittery tones, their black and gray suits perfectly pressed. They stepped out of his way when he approached and didn’t look him in the eye when he passed. A woman he thought was called Linda, or Lisa, held the elevator door open and looked at him with a smile that seemed so forced it must have been painful for her. He stepped in past her and she flinched away, mumbling something that might have been a version of “Good morning.”

Then she started to decide if she should step out of the elevator or ride up with him. She stepped out, back in, then out again then back in, her hand always on the door, holding it open. Others in their gray or black suits approached, saw him, saw her, and decided to take the stairs or a different elevator.

A meeting was waiting for him, and though he wanted more than anything for that meeting not to start, he sighed. The woman jumped out of the elevator as though he’d roared at her. She whimpered an apology while the doors rolled closed in front of her face. She had already pressed the button for his floor for him, so he just stood here, looking down at the richly carpeted floor, avoiding the mirrored surface of the doors, as the elevator lifted him up into the heart of the Edifice—the section that had been renovated to 21st Century standards, the outer ring that made accommodations like electricity, running water, windows, light, air.

The elevator came to stop and the doors opened to reveal his assistant, waiting for him, clutching a leather folder to her chest. He was aware of how beautiful she was. In another time, she would have been a model, a movie star, but in their time, she was his assistant. She looked more scared than usual, and he wondered if it was a good idea his having told her what it meant if Kim Larter called a meeting. Her knowing wouldn’t change it, but at least they could have gone from the elevator to the conference room without her being one breath away from a nervous breakdown.

He shook his head just a little, getting himself into character as they walked.

The entire legal staff was waiting for him in the big conference room—so many that there weren’t chairs for everyone. They had left a chair open for him on one end of the long table. At the other end sat Kim Larter. Four of the five chairs on one long side of the table were vacant. Jason Wendly sat in the middle chair, eyes wide, flickering from face to face. No one made eye contact with him. No one stood within eight feet of him. And it was plain he had no idea why.

With a glance at Jason, he sat, and said, “Kim . . .” Everyone tried hard to seem to be looking each other in the eye without actually having to do it. “The pronouncement?”

Kim Larter nodded, a little faster than she should have. Sweat dotted her upper lip and she was shaking—not just her hands, but her whole body, trembling in her seat. Her suit was black, so wouldn’t show the sweat, but even under layers of deodorant, everyone in the room could smell it on her—smell the terror.

“Why, uh . . .” Jason started. “Am I . . . ?”

“There has been a pronouncement,” Kim said, her voice a little too loud. Everyone subtly moved farther away from Jason, like trees pushed by a sudden gust of wind. Jason’s glazed eyes watered, his body shaking so hard he seemed to be having a seizure. The pleading in his stare was plain and painful. “One of us has failed to procreate and it has been found to be due to a lack of—“ she paused to swallow, maybe to gag— “sperm motility. It calls for blood atonement.”

“Jason,” one of the other lawyers whispered, and Jason screamed.

The sound came up from him like a geyser, blasting out his throat to fill the room with an ear-rattling shriek. The sound drained the blood out of everyone in the room and a few of the weaker ones staggered back, brushing up against the plain gray walls of the conference room.

Then Jason’s skin started to come off. He screamed over and over again, almost barking, squealing as his skin came away from muscles, blood oozing and running every which way as though it was trying to make up its mind which way it should flow. He lived, screaming, for an obscenely long time while he was peeled like an apple by some unseen agency, leaving a quivering, ragged, bloody mess slumped in the chair. Jason lived for almost two minutes more with no skin at all then he rolled to the floor, dead but still quivering, on a hideous bed of his own skin.

The smell of blood mingled with vomit. Someone had vomited—more than one of them—but he had not. He kept his wits about him, barely, and even kept his eyes open. He had watched and registered the demonstration. He had watched a man he’d worked with for nine years skinned alive and he hadn’t screamed or thrown up, or done anything at all to stop it—as if there was anything in this or any world he could have done to stop it. Jason Wendly had been given everything he had been given: a wife, a house, the responsibility to breed. Jason proved unable to live up to that, so he was unable to live.

“That’ll be all, then,” he said, marveling at the sound of his own voice, calm and confident in the electrified air.

He stood and the other lawyers winced away as he passed them. They allowed him to be the first out of the room, letting him get a few steps away before they flooded out after him, a few of them wiping away tears, a few wiping away vomit, and one or two—the younger ones—wiping away smiles. Kim Larter bumped her elbow and turned an ankle trying to get past some of the others. She stumbled and no one moved to help her. Panting like a dog, she made a beeline for her office.

Pretty, petite little April Graham, the youngest of the associates said, “Yeah, man, welcome to R’lyeh.”

The rest of them pretended not to have heard her.

He made for his office, his assistant quivering at his side, and closed the door in her face. He sat down behind his desk and held his breath until black spots danced in front of his eyes. Breathing again, he turned his chair to face the floor-to-ceiling windows and their view of the Seattle skyline, across the Sound, covered in clouds through which dark shapes writhed. The buildings of downtown were slowly but surely being replaced by structures of impossible geometry that made his head hurt and his soul quake just looking at them. So he turned back to his desk and went to work.

It had been twelve years since the lost city of R’lyeh rose from the black depths of the cold Pacific. Twelve years since the beginning of the reign of the Great Cthulhu. Nine years since he had been tasked as one of the Master’s lawyers. And there was still much to be done.

And now I’ll direct you to a post from almost two years ago.

Discuss

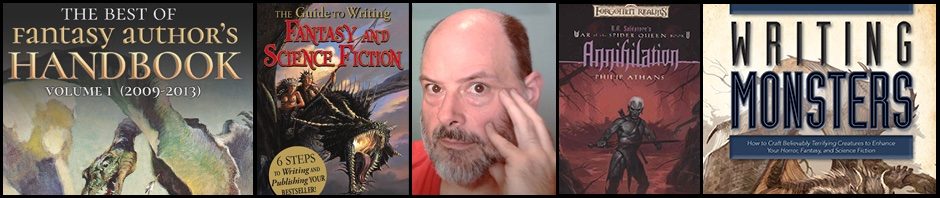

—Philip Athans

Pingback: HORROR AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK—THE HALLOWEEN EDITION | Fantasy Author's Handbook