Is there such a thing as a perfect book? If there is, I haven’t read one, let alone written one. One of the things I’d hoped to accomplish with this blog was not just to promote the book but to supplement it with additional material. This wouldn’t be much of a blog about the writing and publishing process if I just let the printed book speak for itself, so here we go, a part or “step” at a time, digging in to correct mistakes, struggle over inconsistencies, patch in missing information, and resurrect edited text.

STEP ONE: Storytelling

The paragraph on page 15 was written after the editor and/or editorial board decided on this 6-Step approach. I’ve already admitted that I really cringed at that idea. I didn’t want anyone to think that I think creative writing is in any way a step-by-step process. If you didn’t get that from that paragraph, I’ll say it again here: Creative writing is not a step-by-step process. Unfortunately, neither is book marketing, and in some cases you just have to grin and bear it when it comes to how a publisher chooses to position your work.

I won’t rehash the Phil vs. copy editor struggle of world building vs. worldbuilding and bestselling vs. best-selling except to say that I was right and the book as sold is wrong. But it doesn’t alter the message so I promise to get over it if you will.

And another heartfelt thanks to Paul S. Kemp for the quote on page 16, and thank you Ernest Hemingway, wherever you are.

Here’s the introductory text the way it appeared in the first draft. Consider it a sort of historical document, if you will:

The easiest part of writing a novel is the part you’re best at, and the hardest part is the part that you’re worst at. That’s true of anything, from playing sports to gourmet cooking. But when it comes to writing genre fiction, very much including fantasy, storytelling is the heart of it. If you’re a good natural storyteller, like my friend R.A Salvatore, the worldbuilding, the research, sentence structure—the craftsmanship of writing—is something you can learn by listening to advice like you’ll find in this book and others, from helpful editors and English teachers, and so on. If you’re not a good natural storyteller, you’ve got a long, difficult road ahead of you.

Teaching writing is relatively easy, but teaching storytelling is close to impossible. I’ll try anyway, but get ready for a lot of generalities, options, and fuzzy thinking. Though this whole book is really about storytelling—how to create a believable fantasy world and populate it with intriguing characters—this section will cover the superstructure upon which all those details are supported. Idea, theme, plot . . . without them you can tell us all about the political structure of your fantasy world, create a whole new language and alphabet, a rich mythology or fantastical religion, but no one will ever know. You won’t have a book, you’ll have a notebook.

Chapter 4: Start With An Idea

Well, that seems like pretty good advice.

Chapter 4 originally started with these two sentences, cut in the interest of brevity:

Hey, what’s the big idea?

It’s the whole point of even writing a book, that’s what it is. When I say “idea,” I mean the answer to this question: “What is your book about?”

I first ran across that Harlan Ellison anecdote in a science fiction class in high school, and it always struck me as a funny and entirely appropriate response to an impossible to answer question. I dug up the text on the internet, excerpted from the biographical film Dreams With Sharp Teeth. I sent Harlan a letter asking his permission to use the quote. He refuses to use email. A few days later he called me on my cell phone and yelled at me for a few minutes, criticizing the wording of one sentence in the letter then made sternly worded demands that resulted in the legal line in the front matter of the book. I am a huge, huge fan of Harlan Ellison, and I say so in this book, and pretty much anywhere I can. He’s the greatest writer of short stories who ever lived. After a quarter century in and around the publishing business I’ve stopped being star struck by authors, but I have to say, being yelled at on the phone by Harlan Ellison—and he’s yelled at me on the phone a few times now—have been some of the most exciting moments of my life.

Another “battle” with the editor was all these subtitles. They were not in the first draft, but the feeling at the publisher was that people can’t digest large blocks of type and need to stop and start every few paragraphs. I succumbed to the pressure, but still don’t think this is true. Maybe I just don’t want it to be true—especially since each chapter in this book was pretty short as is. Anyway, reading it again, some, though admittedly not all, of these sub-heads still feel like interlopers. The one at the top of page 19 does for sure.

Here’s the sidebar that was cut from this chapter, my sorry attempt at providing a running example, and a cut I was happy was made.

Example World: One Idea, Limitless Potential

So what is the idea for our example novel? I kinda like one of my what ifs from the above section. It really did just come to me as I was typing, but I think I can work with it:

What if the best swordsman in the kingdom lost both his arms?

Here’s a guy who starts the book with a history. We know already that he’s the kingdom’s greatest swordsman, but isn’t anymore—he can’t be, with no arms—or can he? I’m already asking myself questions like, How did he lose his arms? Was it an accident? Was he bested by a superior swordsman? Does he seek revenge against the man (or woman, or monster, or whatever) that took his arms? Was it his own fault? Does his disability put the kingdom in danger? Or was this guy a danger to the kingdom? Is he the hero or the villain? Was he a hero who becomes a villain after losing his arms, or is it the other way around?

Yeah, I think I have some room to play with that one.

Chapter 5: Have Something to Say

This short paragraph was cut from the beginning, I think because it made me sound too glum, as though I was telling you that this is really all too hard and you should just give up. Setting aside how true that is, it did seem a bit discouraging in retrospect:

A heady question, that first one: What does your book teach us? It can be a little intimidating until you stop and think about it. Then it’s at least a little less intimidating. The idea of starting a novel should be a little intimidating. It’s a long, difficult road that very few people can travel and fewer can navigate well.

I actually cited two sources for that Robert E. Howard letter. Here’s the first one, and here’s the second one.

The paragraph immediately following the letter was thought to be too snarky. Judge for yourself:

Hey, wait a minute. The Conan stories were about something? They had a <gasp> point of view? You bet your broadsword they did, and that the author was keenly aware of the same. So, yes, fantasy stories not only can have a message, but like all fiction, inherently must have a message. The subtlety with which that message is conveyed is another matter entirely.

There’s another one of those forced sub-heads at the top of page 22, but the rest of the headings starting with THE TRUE MEANING . . . were not in my first draft, but were a welcome addition. See? It’s not all Phil vs. Editor!

And this chapter’s excised sidebar:

Example World: And the Moral of the Story Is . . .

So we know we’re going to write a science fiction inspired high fantasy tale in which the greatest swordsman in the kingdom loses both his arms (or has lost both his arms). Let’s brainstorm all five categories:

The True Meaning of . . . greatness. He was a terrific swordsman, but what really makes one great? The ability to kill someone really fast? His service to the kingdom as a soldier? His ability to teach his martial art to the next generation of swordsmen?

The Corrupting Influence of . . . fame. Everyone knew he was the greatest swordsman in the kingdom, and everyone wanted a piece of him—and finally they got two pieces: his arms. Once he was proclaimed “the greatest,” did he become (not to put too fine a point on it) a dick? Did he deserve to be permanently “disarmed”?

The Vital Importance of . . . dignity. Having lost his arms, he can’t flash his swords around, but does that mean he crawls into a bottle and feels sorry for himself, or does he stand tall, knowing that he’s more than just his ability to wield a sword, and proves that the true warrior doesn’t need to cut his opponent to win the day.

The Undeniable Power of . . . ingenuity. Okay, so he lost his arms, but does that mean he can never wield a sword again? Not if he’s particularly creative and finds a way to reclaim his power by “thinking outside the box,” and finding a way to be an even better swordsman through his own creativity.

The Eternal Struggle Between . . . mind and body. Are you your arms or your brain? If you lose your arms, even if you make a living as a swordsman, is it all over for you? Maybe our hero realizes that now that he can’t use his body to beat his opponents down physically he’ll have to think harder, outsmart them, or maybe he’ll come to realize that he shouldn’t have been fighting them in the first place. This goes to the eternal struggle between savagery and civilization that Robert E. Howard explored.

Especially since we’re looking for some science fiction elements, I like the idea of the vital importance of ingenuity. Maybe our hero can build himself some steampunky mechanical arms and re-learn how to wield a sword. That might be a little too much like the movie Army of Darkness, but we’ll find a creative take on it, I promise.

Chapter 6: Develop a Plot

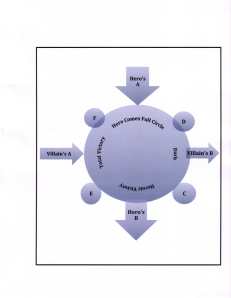

Ah, the diagram. How much suffering over the diagram? I’ve drawn this on white boards and in notes to authors more times than I can count, but there was no budget for a graphic designer for this book, so I was told that if I wanted the diagram I had to do it myself. I’m not a graphic designer. I’ve worked with some of the best in the business, which is how I know I’m not one, but I did my best. This was actually assembled using Microsoft Word—that’s how not a graphic designer I am. A graphic designer would have lined up the circles and arrows with any precision at all, for instance. Me, not being a graphic designer, did not.

I had to make a gray version of it, but it started out blue:

I wish I’d saved some of the earlier versions. Some of them were hilarious, especially the hand-drawn versions. In retrospect they might have given the book a retro charm, like an old Judges Guild supplement, but alas. . . .

Anyway, I still think the diagram gets the point across.

Following the diagram is another example of the positive application of sub-heads. I think they make interpreting the diagram lots more clear than my original big block of text.

And the sidebar:

Example World: Plotting Out a Plot

We already know who our hero is, the finest swordsman in the realm, but he’s lost his arms. First, let’s decide where we hope our story will end up. This is a high fantasy tale with some SF elements—that leaves us all sorts of room. But I think we’d better stick to something a little less controversial, and though I’m a big fan of “dark,” I recognize that I’m kind of in the minority on that one, but come on, we can get a little dark, can’t we?

Let’s say that we want our hero and villain to end up somewhere on the dark side of the heroic victory zone, more or less point C.

Our hero’s A is he’s the finest swordsman in all the realms, supremely self-confident and at the top of the world. He’s fiercely loyal to the aging emperor, a man he respects and loves like a father. He intends to marry the emperor’s daughter and one day become king, because the emperor has no son. That kinda sounds like the movie Gladiator, but just like the Army of Darkness bit, we’ll find lots of ways to make it our own.

The villain begins as a rival swordsman who was disgraced years ago and driven into exile. He plans to return to the empire, assassinate the emperor, force the princess to marry him, and seize control of the empire that had turned its back on him.

When these two men first face off, at the conflict point, the treacherous villain uses a new, high-tech power sword the hero isn’t familiar with. This new weapon tips the balance enough so that our hero’s arms are severed. The villain, certain of his success having eliminated the emperor’s champion, succeeds in murdering the emperor and seizing the throne, but the princess escapes.

The hero has been knocked off his trajectory, and bumped closer to the villain’s plans. But the princess finds him and inspires him to a new goal—now A-C instead of A-B—to defeat the man who defeated him, and save the empire.

Chapter 7: Know When to Stop

Here’s some good stuff that was cut from the beginning of this chapter because the book was running long:

Years ago I was on a panel at a convention with three other SF/fantasy authors, including the late Chris Bunch. The topic was why fantasy books always seem to come in threes. We started going down the table trying to answer that, and the best I could come up with was that The Lord of the Rings was published as a trilogy, and that’s become the prototype for all fantasy novels that came after it. The Lord of the Rings was a trilogy, therefore fantasy-equals-trilogy.

I’m not saying I was right, but I still can’t think of a better answer. Later, the guy who organized the panel admitted he was kind of stretching for a subject. The discussion very quickly left the question of fantasy in threes and ended up touching on a wide variety of topics, led by Chris Bunch’s huge, funny, irreverent personality.

The reason I’m starting this section with that story is so I can start up front with my feeling that there’s no really good reason that fantasies should come in trilogies, even having written one myself. This bit will be a little bit light on absolutes, and more along the lines of: you tell me. But with a standard caution: think carefully, be smart, and know when to commit yourself, and when to let your readers decide how long you stay in one world.

I honestly can’t remember Chris Bunch’s answer to that question, I think he just dismissed it off hand, but I ran it past a few other experts.

The convention was Northwest Book Fest, and I don’t remember the year, but it was after we moved to Seattle and before my son was born so between 1997 and 2000.

Example World: Taking my own Advice

My armless swordsman character has “beloved star of a multi-book franchise” written all over him, but I need to listen to my own advice, and keep thinking in terms of this one novel. I’ll take Paul’s advice as well, though, and make sure that there are plenty of hooks I can come back to and hang at least parts of follow-up novels on.

I’m even going to think about this in terms of a title.

Sometimes you can build a series title right into the title of the first book. Movies do that all the time, since it’s extremely rare that a movie studio will bet what now can be hundreds of millions of dollars on a movie series before they know if anyone is going to go to the first one. Star Wars is the classic example. Before the first movie became the massive success it was, there was no Episode IV, it was just Star Wars, then Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, and so on.

Is this too early to come up with a title for my armless swordsman novel? Maybe, but not too early for a placeholder. Lets start thinking of this book as:

Armless Swordsman.

Then if there’s a sequel it could be: Blood Red Steel: Armless Swordsman Book II, then The Dark Darkness: Armless Swordsman Book III, and so on until thirty years from now one of my kids (maybe in collaboration with Kevin J. Anderson) writes: The Final Dead Horse is Beaten: Armless Swordsman Book XXIX.

I can roll with that—for now.

The first draft contained this footnote, an aside to my editor, Peter Archer: “Peter—tell me if this is too snarky a jab at Kevin Anderson and Brian Herbert. I want Kevin to write D&D stuff. Will this make him hate me?”

Yeah, hi, Kevin, please don’t hate me—you know I love you, man.

Chapter 8: Learn How to Write

Wow, a big subject for one short chapter, but y’know, this can’t be the only book on writing you need to read if you really want to write for a living.

The sub-heads added throughout this chapter were a big help, too.

This one was pretty much entirely intact from the first draft, and there was no example world sidebar for this chapter, so I think that wraps it up for Step One!

—Philip Athans

Pingback: thebookishowl.com » Blog Archive » “The Guide to Writing Fantasy and Science Fiction” by Philip Athans (Reviewed by David Craddock)