This week we continue a five-part series inspired by H.P. Lovecraft’s essay “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction” in which one paragraph stood out for me as the beginnings of a horror/weird fantasy manifesto:

Each weird story—to speak more particularly of the horror type—seems to involve five definite elements: (a) some basic, underlying horror or abnormality—condition, entity, etc.—, (b) the general effects or bearings of the horror, (c) the mode of manifestation—object embodying the horror and phenomena observed—, (d) the types of fear-reaction pertaining to the horror, and (e) the specific effects of the horror in relation to the given set of conditions.

If you haven’t read part one yet, here’s the link. In this penultimate chapter we’ll dig deeper into the fourth point:

(d) the types of fear-reaction pertaining to the horror

I take this to mean: What makes this thing scary.

There are all sorts of reasons to be afraid of something, including things that turn out not to be true, or turn out not to be so bad or even beneficial when all is said and done. Even if the ultimate reveal of your monster story is that the monster is actually friendly and here to help us, if you want your characters (and by extension, your readers) to be afraid of it along the way, you’ve got some work to do.

There are all sorts of reasons to be afraid of something, including things that turn out not to be true, or turn out not to be so bad or even beneficial when all is said and done. Even if the ultimate reveal of your monster story is that the monster is actually friendly and here to help us, if you want your characters (and by extension, your readers) to be afraid of it along the way, you’ve got some work to do.

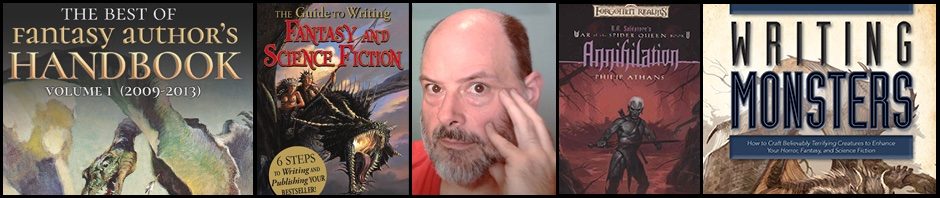

A full chapter in my book Writing Monsters is called, appropriately, “What Makes a Monster Scary?” and you can read that here. There I actually break down the ten most common phobias to look at what psychologists have identified are common fears, however irrational. Then I did my best to break down what makes a monster scary and got it down to any combination of one, some, or all of these seven traits:

- They are unpredictable

- They have a disturbing capacity for violence

- They exhibit “otherness”

- They are amoral

- They are beyond our control

- They are terrifying in appearance

- They turn us into prey

I’ll let you go back to the book or to that post for more on each point, but I’d like add an eighth and that’s that they show us something terrifying inside of us.

In the same way that your “one weird thing,” be it monster, artifact, spell, or what have you, can bring out the good or evil in the people who encounter it, revealing their strengths and weaknesses, sometimes the “weird thing” has been inside us all along and the horror begins when that’s revealed. Or better yet, is sustained while we worry that it might be revealed. More on that in my post Surprise vs. Suspense vs. Writing Monsters.

This is the idea of transformation—the fear of turning into a monster, or of having your personality, your sense of self, your individual agency taken from you. This is why Invasion of the Body Snatchers or Night of the Living Dead are scary—we’re either taken over by something that turns us into monsters, or some amoral, non-intelligent cause (a plague, etc.) transforms us into monsters.

Going back to role-playing games for a second week, this is where you get into a monster’s “special attacks.” Likewise, the effects of a particular magical item or spell. What does this thing do to you? Does it bite you, eat you, absorb you, enslave you? These all sound scary to me, but a simple statement like “zombies eat living humans,” isn’t going to be enough to put the fear of zombies into your readers.

In a post from last May I called on you to Show Your Villain Being Villainous, and I should have added to that: Show your monster being monstrous, show your one weird thing being weird, or as Chuck Wendig said in “25 Things You Should Know About Writing Horror”:

Beneath plot and beneath story is a greasy, grimy subtextual layer of pacing—the tension and recoil of dread and revulsion. Dread is a kind of septic fear, a grim certainty that bad things are coming. Revulsion occurs when we see how these bad things unfold. We know that the monster is coming, and at some point we must see the wretchedness of the beast laid bare. Dread, revulsion, dread, revulsion.

Showing the emotion of fear is as difficult as any other emotion, and though it feels as though I’m sending you to other posts an awful lot this week, I did get into that in my series on emotions, namely fear.

Here’s part of a scene from my horror novel Completely Broken, in which I attempted to layer into one scene various fears—fear of enslavement, fear of the unknown or of the seemingly impossible, and fear of physical pain and mutilation:

Gilroy’s reflection studied him with Jake’s unyielding stare. Like he kept track of sleepless hours, he kept track of Jake’s visits—twelve so far, not counting the times he had to huddle in a corner and not move or the demons would see him. The demons came dozens, maybe hundreds of times, and he never saw their faces. Jake had come only twelve times, though Gilroy couldn’t remember a time before Jake. Before he was a slave.

Jake looked away and Gilroy gasped, longing for the thing he most feared in the world: Jake’s stare, Jake’s attention. The demon in the bathtub moaned, or laughed, or growled—some kind of sound meant to convey reproach.

“I’ll…” Gilroy managed to choke out, “do it.”

The reflection met Gilroy’s eyes again and smiled. There was a line of infected black around the nearly orange teeth.

Do they look that bad? Gilroy thought. Do my teeth really look that bad?

“I know,” came rumbling from the mirror, “but you hesitated.”

“I hesitated,” Gilroy repeated, beginning to cry.

The demon in the bathtub started to pull the shower curtain down. The cheap, thin nylon stretched at the rings.

“You will lose…”

Gilroy wept. He might have cried like that when he was a newborn baby. His lips pulled back until he thought they’d snap.

“Your teeth,” Jake said.

The reflection came out. Jake broke the line of the mirror, but there was no shattering of glass. Tears and terror kept Gilroy from seeing the twisted, hideous mockery of his own face hurl itself at him. Jake’s grotesque, stinking mouth opened over Gilroy’s and came down so hard and so fast that his teeth, almost every last one of them, shattered in his gums as if they were made of glass. The pain was an explosion that made his head burst into dizzying light. Jake’s face withdrew, spitting teeth as it slid back into the mirror. Teeth and blood showered Gilroy’s face and he closed his eyes tightly. He’d never imagined such pain. His teeth, his whole mouth, were ruined.

The demon in the bathtub screamed, a shrill whistling sound, and thrashed madly against the cracking porcelain. The curtain whipped around but didn’t fall.

Gilroy looked away, put his hands to the ruin of his mouth, and sat down hard on the tile floor. The demon in the bathtub was gone all at once. He continued to cry, letting the reflection’s last “Finish it…” trail off into silence.

When Gilroy came out of the bathroom he came out screaming. He stabbed Howard over and over, the blood from his mouth mixing with his jerking victim’s. It took three minutes for Howard to die. Gilroy laughed at the strong man’s last breath, his own blood blowing out in strings on the wind of his vacant cackling.

I tried my best to keep this about my POV character, Gilroy, throughout. It’s his experience of the demons that haunt him, that make demands of him, and that punish any transgression.

Most of all, it’s never going to be enough to simply say: Galen was scared.

That’s telling us he’s scared. Your job is to show us he’s scared so we (your readers) are scared right along with him. Your readers and your characters should be sharing the experience of being in that moment, in that place and time, with that thing. In my Horror Intensive course I suggest finding your favorite horror movie—one that’s particularly well acted at least—and when you get to the close-up of one of the actors being scared, pause it, run it back, study it. What does it look like, in that person’s face, eyes, body, to be scared? Describe that on paper then run it back and add a layer, then find another scene like it, maybe even in a different movie and try it again.

I think we’ve all been scared before—what a lovely life you’ve had if you haven’t!—but not all of us have experienced real mortal terror. I’m not talking about the fear of the top of the roller coaster or the phobic nervousness of a rattling elevator or the childish dread of wait till daddy comes home—I mean the sort of fear a character confronted with an honest to God monster might feel, fear akin to: “This shark is about to bite my frickin’ head off!” A good actor might have somehow channeled that—let that be your guide, or at least your starting point.

And if you have felt that fear and can access the memory of it while remaining reasonably psychologically healthy—and after all, remaining reasonably psychologically healthy is all any writer can ask for—then I can’t wait to read your horror novel.

—Philip Athans

Pingback: LOVECRAFT’S FIVE DEFINITE ELEMENTS, PART 3: WHAT IT ACTUALLY DOES | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Truly helpful!

Pingback: Writing Links 4/3/17 – Where Genres Collide

Pingback: A Different, More Terrifying Cosmos: Our Brave New Lovecraftian World - OnePeterFive

Pingback: HORROR AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK—THE HALLOWEEN EDITION | Fantasy Author's Handbook

Pingback: HORROR AUTHOR’S HANDBOOK—THE HALLOWEEN EDITION – Zack